I’ll start with some tech talk first. Feel free to jump to the usage example further down if you are here for the edge bundling plugin.

As you certainly know, QGIS 3 brings a lot of improvements and under-the-hood changes. One of those changes affects all Python scripts. They need to be updated to Python 3 and the new PyQGIS API. (See the official migration guide for details.)

To get ready for the big 3.0 release, I’ve started porting my Processing tools. The edge bundling script is my first candidate for porting to QGIS 3. I also wanted to use this opportunity to “upgrade” from a simple script to a plugin that integrates into Processing.

I used Alexander Bruy’s “prepair for Processing” plugin as a template but you can also find an example template in your Processing folder. (On my system, it is located in C:\OSGeo4W64\apps\qgis-dev\python\plugins\processing\algs\exampleprovider.)

Since I didn’t want to miss the advantages of a good IDE, I set up PyCharm as described by Heikki Vesanto. This will give you code completion for Python 3 and PyQGIS which is very helpful for refactoring and porting. (I also tried Eclipse with PyDev but if you don’t have a favorite IDE yet, I find PyCharm easier to install and configure.)

My PyCharm startup script qgis3_pycharm.bat is a copy of C:\OSGeo4W64\bin\python-qgis-dev.bat with the last line altered to start PyCharm:

@echo off

call "%~dp0\o4w_env.bat"

call qt5_env.bat

call py3_env.bat

@echo off<span data-mce-type="bookmark" style="display: inline-block; width: 0px; overflow: hidden; line-height: 0;" class="mce_SELRES_start"></span>

path %OSGEO4W_ROOT%\apps\qgis-dev\bin;%PATH%

set QGIS_PREFIX_PATH=%OSGEO4W_ROOT:\=/%/apps/qgis-dev

set GDAL_FILENAME_IS_UTF8=YES

rem Set VSI cache to be used as buffer, see #6448

set VSI_CACHE=TRUE

set VSI_CACHE_SIZE=1000000

set QT_PLUGIN_PATH=%OSGEO4W_ROOT%\apps\qgis-dev\qtplugins;%OSGEO4W_ROOT%\apps\qt5\plugins

set PYTHONPATH=%OSGEO4W_ROOT%\apps\qgis-dev\python;%PYTHONPATH%

start /d "C:\Program Files\JetBrains\PyCharm\bin\" pycharm64.exe

In PyCharm File | Settings, I configured the OSGeo4W Python 3.6 interpreter and added qgis-dev and the plugin folder to its path:

With this setup done, we can go back to the code.

I first resolved all occurrences of import * in my script to follow good coding practices. For example:

from qgis.core import *

became

from qgis.core import QgsFeature, QgsPoint, QgsVector, QgsGeometry, QgsField, QGis<span data-mce-type="bookmark" style="display: inline-block; width: 0px; overflow: hidden; line-height: 0;" class="mce_SELRES_start"></span>

in this PR.

I didn’t even run the 2to3 script that is provided to make porting from Python 2 to Python 3 easier. Since the edge bundling code is mostly Numpy, there were almost no changes necessary. The only head scratching moment was when Numpy refused to add a map() return value to an array. So (with the help of Stackoverflow of course) I added a work around to convert the map() return value to an array as well:

flocal_x = map(forcecalcx, subtr_x, subtr_y, distance)

electrostaticforces_x[e_idx, :] += np.array(list(flocal_x))

The biggest change related to Processing is that the VectorWriter has been replaced by a QgsFeatureSink. It’s defined as a parameter of the edgebundling QgsProcessingAlgorithm:

self.addParameter(QgsProcessingParameterFeatureSink(

self.OUTPUT,

self.tr("Bundled edges"),

QgsProcessing.TypeVectorLine)

)

And when the algorithm is run, the sink is filled with the output features:

(sink, dest_id) = self.parameterAsSink(

parameters, self.OUTPUT, context,

source.fields(), source.wkbType(), source.sourceCrs()

)

# code that creates features

sink.addFeature(feat, QgsFeatureSink.FastInsert)

The ported plugin is available on Github.

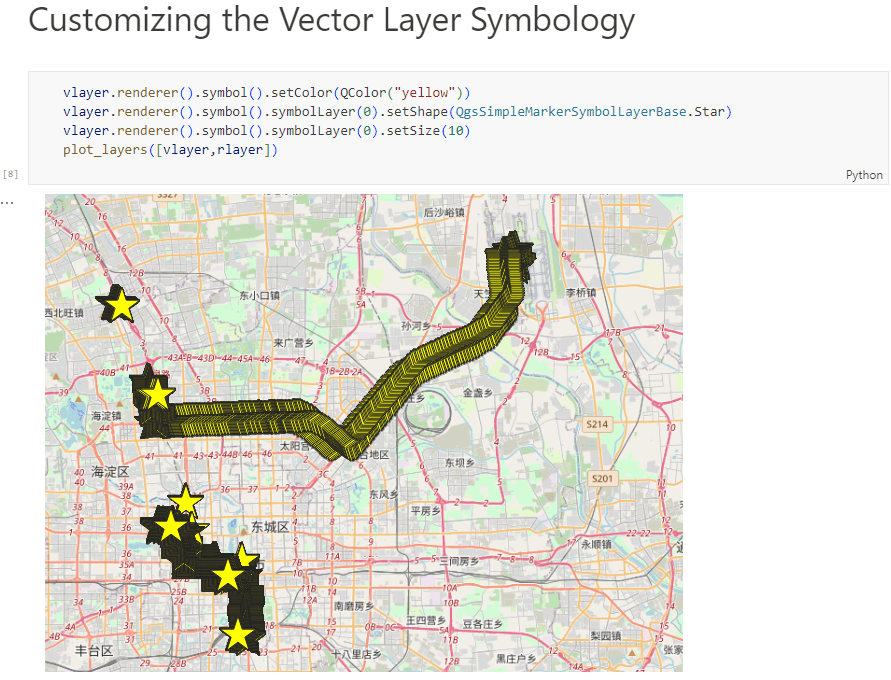

The edge bundling plugin in action

I haven’t uploaded the plugin to the official plugin repository yet, but you can already download if from Github and give it a try:

For this example, I’m using taxi pick-up and drop-off data provided by the NYC Taxi & Limousine Commission. I downloaded the January 2017 green taxi data and extracted all trips for the 1st of January. Then I created origin-destination (OD) lines using the QGIS virtual layer feature:

To get an interesting subset of the data, I extracted only those OD flows that cross the East River and have a count of at least 5 taxis:

Now the data is ready for bundling.

If you have installed the edge bundling plugin, the force-directed edge bundling algorithm should be available in the Processing toolbox. The UI of the edge bundling algorithm looks pretty much the same as it did for the QGIS 2 Processing script:

Since this is a small dataset with only 148 OD flows, the edge bundling processes is pretty quick and we can explore the results:

Beyond this core edge bundling algorithm, the repository also contains two more scripts that still need to be ported. They include dependencies on sklearn, so it will be interesting to see how straightforward it is to convert them.