The city of Vienna provides both subdistrict geometries and population statistics. Mapping the city’s population density should be straightforward, right? Let’s see …

We should be able to join on ZBEZ and SUB_DISTRICT_CODE, check! But what about the actual population counts? Unfortunately, there is no file which simply lists population per subdistrict. The file I found contains four lines for each subdistrict: females 2011, males 2011, females 2012 and males 2012. That’s not the perfect format for mapping general population density.

A quick way to prepare our input data is applying pivot tables, eg. in Open Office: The goal is to have one row per subdistrict and columns for population in 2011 and 2012:

Export as CSV, add CSVT and load into QGIS. Finally, we can join geometries and CSV table:

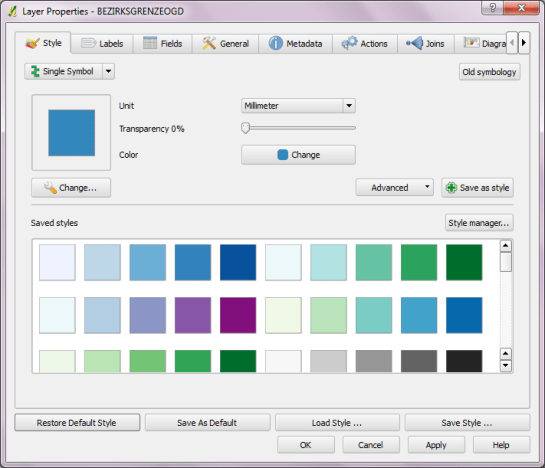

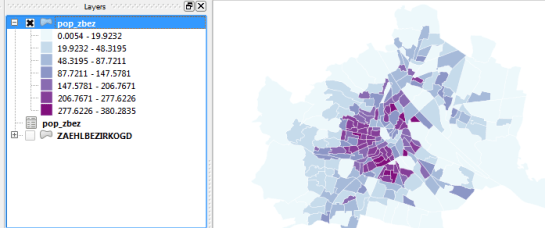

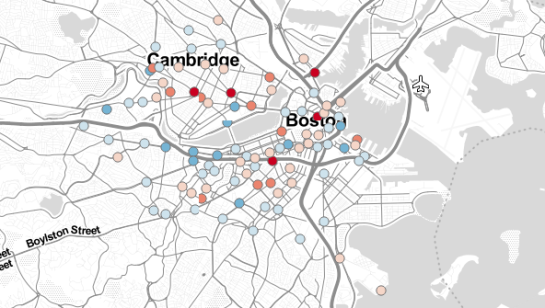

A quick look at the joined data confirms that each subdistrict now has a population value. But visualizing absolute values results in misleading maps. Big subdistricts with only average density will overrule smaller but much denser subdistricts:

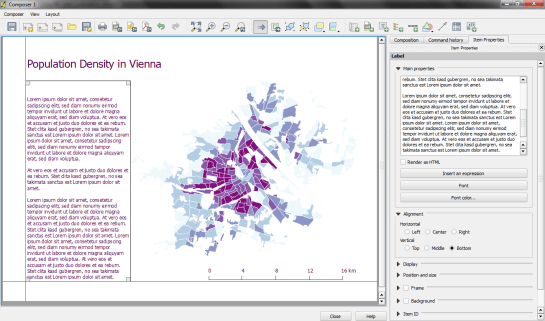

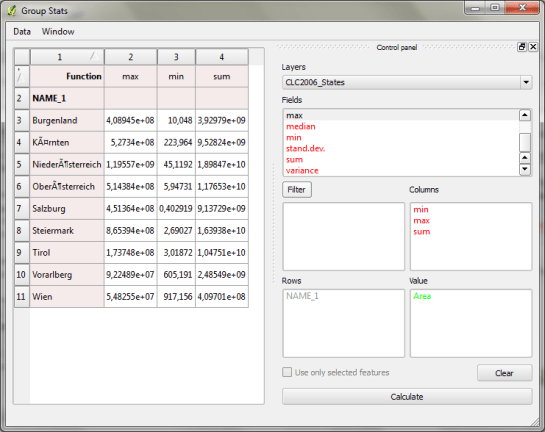

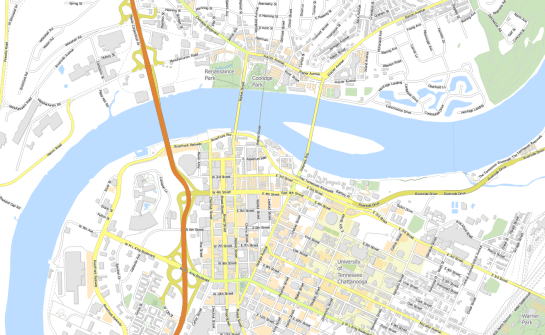

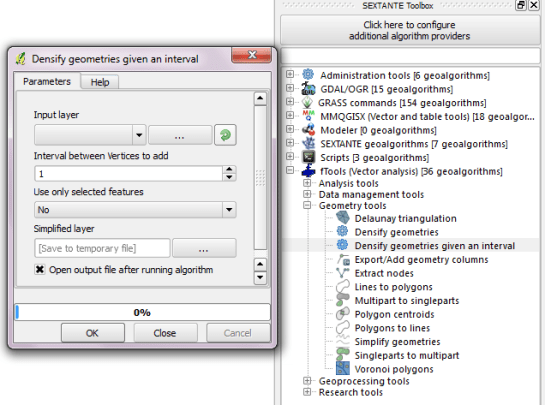

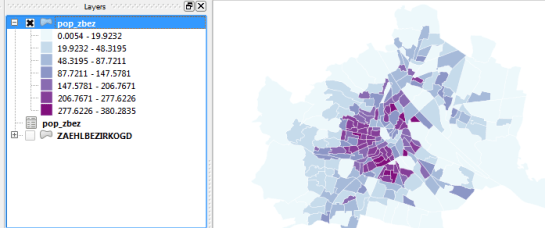

That’s why we need to calculate population density. This is easy to do using Field Calculator. The subdistrict file already contains area values but even if they were missing, we could calculate it using the $area operator: "pop2012" / ($area / 10000). The resulting population density in population per ha finally shows which subdistricts are the most densely populated:

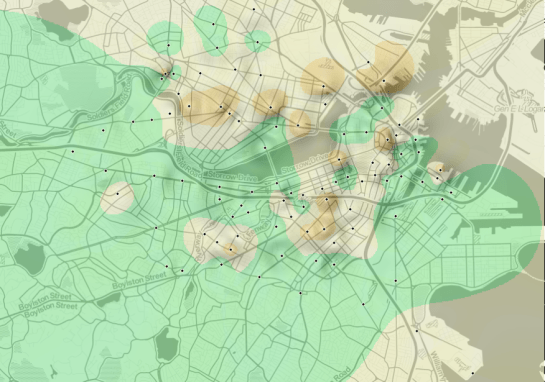

One could argue that this is still no accurate representation of population density: Big parts of some subdistricts are actually covered by water – especially along the Danube – and therefore uninhabited. There are also big parks which could be excluded from the subdistrict area. But that’s going to be the topic of another post.

If you want to use my results so far, you can download the GeoJSON file from Github.