In a previous post, I showed how to use docker to run a single application (GeoServer) in a container and connect to it from your local QGIS install. Today’s post is about running a whole bunch of containers that interact with each other. More specifically, I’m using the images provided by Geodocker. The Geodocker repository provides a setup containing Accumulo, GeoMesa, and GeoServer. If you are not familiar with GeoMesa yet:

GeoMesa is an open-source, distributed, spatio-temporal database built on a number of distributed cloud data storage systems … GeoMesa aims to provide as much of the spatial querying and data manipulation to Accumulo as PostGIS does to Postgres.

The following sections show how to load data into GeoMesa, perform basic queries via command line, and finally publish data to GeoServer. The content is based largely on two GeoMesa tutorials: Geodocker: Bootstrapping GeoMesa Accumulo and Spark on AWS and Map-Reduce Ingest of GDELT, as well as Diethard Steiner’s post on Accumulo basics. The key difference is that this tutorial is written to be run locally (rather than on AWS or similar infrastructure) and that it spells out all user names and passwords preconfigured in Geodocker.

This guide was tested on Ubuntu and assumes that Docker is already installed. If you haven’t yet, you can install Docker as described in Install using the repository.

To get Geodocker set up, we need to get the code from Github and run the docker-compose command:

$ git clone https://github.com/geodocker/geodocker-geomesa.git

$ cd geodocker-geomesa/geodocker-accumulo-geomesa/

$ docker-compose up

This will take a while.

When docker-compose is finished, use a second console to check the status of all containers:

$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

4a238494e15f quay.io/geomesa/accumulo-geomesa:latest "/sbin/entrypoint...." 19 hours ago Up 23 seconds geodockeraccumulogeomesa_accumulo-tserver_1

e2e0df3cae98 quay.io/geomesa/accumulo-geomesa:latest "/sbin/entrypoint...." 19 hours ago Up 22 seconds 0.0.0.0:50095->50095/tcp geodockeraccumulogeomesa_accumulo-monitor_1

e7056f552ef0 quay.io/geomesa/accumulo-geomesa:latest "/sbin/entrypoint...." 19 hours ago Up 24 seconds geodockeraccumulogeomesa_accumulo-master_1

dbc0ffa6c39c quay.io/geomesa/hdfs:latest "/sbin/entrypoint...." 19 hours ago Up 23 seconds geodockeraccumulogeomesa_hdfs-data_1

20e90a847c5b quay.io/geomesa/zookeeper:latest "/sbin/entrypoint...." 19 hours ago Up 24 seconds 2888/tcp, 0.0.0.0:2181->2181/tcp, 3888/tcp geodockeraccumulogeomesa_zookeeper_1

997b0e5d6699 quay.io/geomesa/geoserver:latest "/opt/tomcat/bin/c..." 19 hours ago Up 22 seconds 0.0.0.0:9090->9090/tcp geodockeraccumulogeomesa_geoserver_1

c17e149cda50 quay.io/geomesa/hdfs:latest "/sbin/entrypoint...." 19 hours ago Up 23 seconds 0.0.0.0:50070->50070/tcp geodockeraccumulogeomesa_hdfs-name_1

At the time of writing this post, the Geomesa version installed in this way is 1.3.2:

$ docker exec geodockeraccumulogeomesa_accumulo-master_1 geomesa version

GeoMesa tools version: 1.3.2

Commit ID: 2b66489e3d1dbe9464a9860925cca745198c637c

Branch: 2b66489e3d1dbe9464a9860925cca745198c637c

Build date: 2017-07-21T19:56:41+0000

Loading data

First we need to get some data. The available tutorials often refer to data published by the GDELT project. Let’s download data for three days, unzip it and copy it to the geodockeraccumulogeomesa_accumulo-master_1 container for further processing:

$ wget http://data.gdeltproject.org/events/20170710.export.CSV.zip

$ wget http://data.gdeltproject.org/events/20170711.export.CSV.zip

$ wget http://data.gdeltproject.org/events/20170712.export.CSV.zip

$ unzip 20170710.export.CSV.zip

$ unzip 20170711.export.CSV.zip

$ unzip 20170712.export.CSV.zip

$ docker cp ~/Downloads/geomesa/gdelt/20170710.export.CSV geodockeraccumulogeomesa_accumulo-master_1:/tmp/20170710.export.CSV

$ docker cp ~/Downloads/geomesa/gdelt/20170711.export.CSV geodockeraccumulogeomesa_accumulo-master_1:/tmp/20170711.export.CSV

$ docker cp ~/Downloads/geomesa/gdelt/20170712.export.CSV geodockeraccumulogeomesa_accumulo-master_1:/tmp/20170712.export.CSV

Loading or importing data is called “ingesting” in Geomesa parlance. Since the format of GDELT data is already predefined (the CSV mapping is defined in geomesa-tools/conf/sfts/gdelt/reference.conf), we can ingest the data:

$ docker exec geodockeraccumulogeomesa_accumulo-master_1 geomesa ingest -c geomesa.gdelt -C gdelt -f gdelt -s gdelt -u root -p GisPwd /tmp/20170710.export.CSV

$ docker exec geodockeraccumulogeomesa_accumulo-master_1 geomesa ingest -c geomesa.gdelt -C gdelt -f gdelt -s gdelt -u root -p GisPwd /tmp/20170711.export.CSV

$ docker exec geodockeraccumulogeomesa_accumulo-master_1 geomesa ingest -c geomesa.gdelt -C gdelt -f gdelt -s gdelt -u root -p GisPwd /tmp/20170712.export.CSV

Once the data is ingested, we can have a look at the the created table by asking GeoMesa to describe the created schema:

$ docker exec geodockeraccumulogeomesa_accumulo-master_1 geomesa describe-schema -c geomesa.gdelt -f gdelt -u root -p GisPwd

INFO Describing attributes of feature 'gdelt'

globalEventId | String

eventCode | String

eventBaseCode | String

eventRootCode | String

isRootEvent | Integer

actor1Name | String

actor1Code | String

actor1CountryCode | String

actor1GroupCode | String

actor1EthnicCode | String

actor1Religion1Code | String

actor1Religion2Code | String

actor2Name | String

actor2Code | String

actor2CountryCode | String

actor2GroupCode | String

actor2EthnicCode | String

actor2Religion1Code | String

actor2Religion2Code | String

quadClass | Integer

goldsteinScale | Double

numMentions | Integer

numSources | Integer

numArticles | Integer

avgTone | Double

dtg | Date (Spatio-temporally indexed)

geom | Point (Spatially indexed)

User data:

geomesa.index.dtg | dtg

geomesa.indices | z3:4:3,z2:3:3,records:2:3

geomesa.table.sharing | false

In the background, our data is stored in Accumulo tables. For a closer look, open an interactive terminal in the Accumulo master image:

$ docker exec -i -t geodockeraccumulogeomesa_accumulo-master_1 /bin/bash

and open the Accumulo shell:

# accumulo shell -u root -p GisPwd

When we store data in GeoMesa, there is not only one table but several. Each table has a specific purpose: storing metadata, records, or indexes. All tables get prefixed with the catalog table name:

root@accumulo> tables

accumulo.metadata

accumulo.replication

accumulo.root

geomesa.gdelt

geomesa.gdelt_gdelt_records_v2

geomesa.gdelt_gdelt_z2_v3

geomesa.gdelt_gdelt_z3_v4

geomesa.gdelt_queries

geomesa.gdelt_stats

By default, GeoMesa creates three indices:

Z2: for queries with a spatial component but no temporal component.

Z3: for queries with both a spatial and temporal component.

Record: for queries by feature ID.

But let’s get back to GeoMesa …

Querying data

Now we are ready to query the data. Let’s perform a simple attribute query first. Make sure that you are in the interactive terminal in the Accumulo master image:

$ docker exec -i -t geodockeraccumulogeomesa_accumulo-master_1 /bin/bash

This query filters for a certain event id:

# geomesa export -c geomesa.gdelt -f gdelt -u root -p GisPwd -q "globalEventId='671867776'"

Using GEOMESA_ACCUMULO_HOME = /opt/geomesa

id,globalEventId:String,eventCode:String,eventBaseCode:String,eventRootCode:String,isRootEvent:Integer,actor1Name:String,actor1Code:String,actor1CountryCode:String,actor1GroupCode:String,actor1EthnicCode:String,actor1Religion1Code:String,actor1Religion2Code:String,actor2Name:String,actor2Code:String,actor2CountryCode:String,actor2GroupCode:String,actor2EthnicCode:String,actor2Religion1Code:String,actor2Religion2Code:String,quadClass:Integer,goldsteinScale:Double,numMentions:Integer,numSources:Integer,numArticles:Integer,avgTone:Double,dtg:Date,*geom:Point:srid=4326

d9e6ab555785827f4e5f03d6810bbf05,671867776,120,120,12,1,UNITED STATES,USA,USA,,,,,,,,,,,,3,-4.0,20,2,20,8.77192982456137,2007-07-13T00:00:00.000Z,POINT (-97 38)

INFO Feature export complete to standard out in 2290ms for 1 features

If the attribute query runs successfully, we can advance to some geo goodness … that’s why we are interested in GeoMesa after all … and perform a spatial query:

# geomesa export -c geomesa.gdelt -f gdelt -u root -p GisPwd -q "CONTAINS(POLYGON ((0 0, 0 90, 90 90, 90 0, 0 0)),geom)" -m 3

Using GEOMESA_ACCUMULO_HOME = /opt/geomesa

id,globalEventId:String,eventCode:String,eventBaseCode:String,eventRootCode:String,isRootEvent:Integer,actor1Name:String,actor1Code:String,actor1CountryCode:String,actor1GroupCode:String,actor1EthnicCode:String,actor1Religion1Code:String,actor1Religion2Code:String,actor2Name:String,actor2Code:String,actor2CountryCode:String,actor2GroupCode:String,actor2EthnicCode:String,actor2Religion1Code:String,actor2Religion2Code:String,quadClass:Integer,goldsteinScale:Double,numMentions:Integer,numSources:Integer,numArticles:Integer,avgTone:Double,dtg:Date,*geom:Point:srid=4326

139346754923c07e4f6a3ee01a3f7d83,671713129,030,030,03,1,NIGERIA,NGA,NGA,,,,,LIBYA,LBY,LBY,,,,,1,4.0,16,2,16,-1.4060533085217,2017-07-10T00:00:00.000Z,POINT (5.43827 5.35886)

9e8e885e63116253956e40132c62c139,671928676,042,042,04,1,NIGERIA,NGA,NGA,,,,,OPEC,IGOBUSOPC,,OPC,,,,1,1.9,5,1,5,-0.90909090909091,2017-07-10T00:00:00.000Z,POINT (5.43827 5.35886)

d6c6162d83c72bc369f68bcb4b992e2d,671817380,043,043,04,0,OPEC,IGOBUSOPC,,OPC,,,,RUSSIA,RUS,RUS,,,,,1,2.8,2,1,2,-1.59453302961275,2017-07-09T00:00:00.000Z,POINT (5.43827 5.35886)

INFO Feature export complete to standard out in 2127ms for 3 features

Functions that can be used in export command queries/filters are (E)CQL functions from geotools for the most part. More sophisticated queries require SparkSQL.

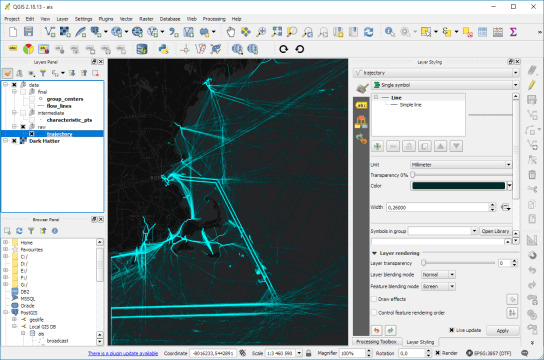

Publishing GeoMesa tables with GeoServer

To view data in GeoServer, go to http://localhost:9090/geoserver/web. Login with admin:geoserver.

First, we create a new workspace called “geomesa”.

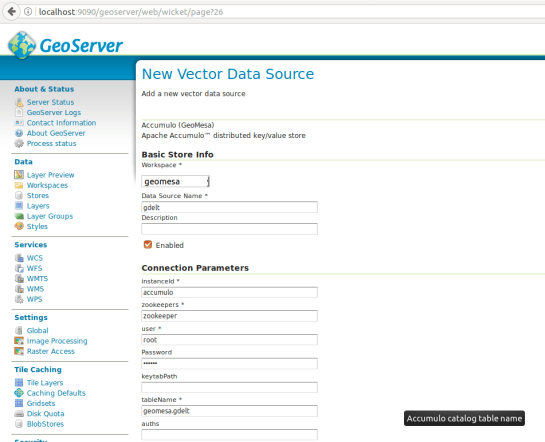

Then, we can create a new store of type Accumulo (GeoMesa) called “gdelt”. Use the following parameters:

instanceId = accumulo

zookeepers = zookeeper

user = root

password = GisPwd

tableName = geomesa.gdelt

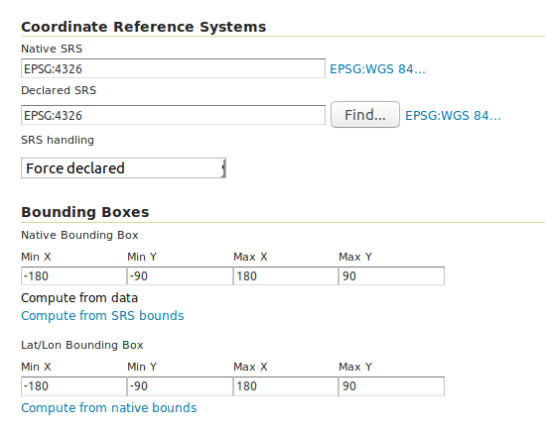

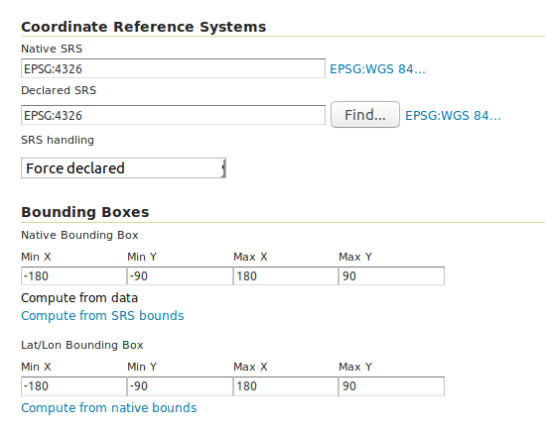

Then we can configure a Layer that publishes the content of our new data store. It is good to check the coordinate reference system settings and insert the bounding box information:

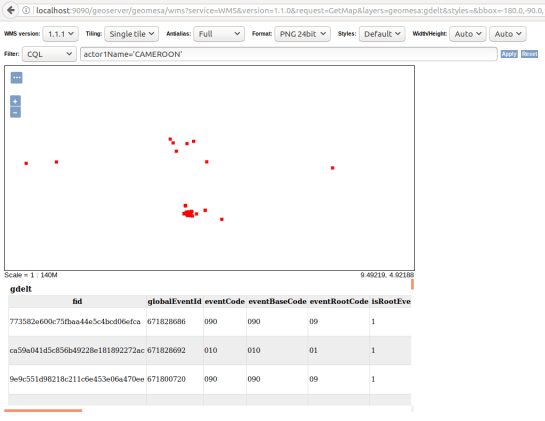

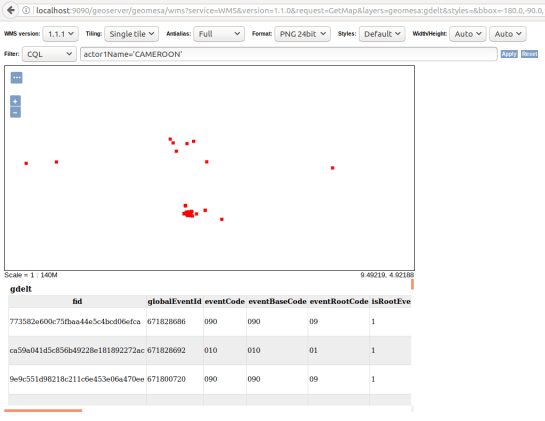

To preview the WMS, go to GeoServer’s preview:

http://localhost:9090/geoserver/geomesa/wms?service=WMS&version=1.1.0&request=GetMap&layers=geomesa:gdelt&styles=&bbox=-180.0,-90.0,180.0,90.0&width=768&height=384&srs=EPSG:4326&format=application/openlayers&TIME=2017-07-10T00:00:00.000Z/2017-07-10T01:00:00.000Z#

Which will look something like this:

GeoMesa data filtered using CQL in GeoServer preview

For more display options, check the official GeoMesa tutorial.

If you check the preview URL more closely, you will notice that it specifies a time window:

&TIME=2017-07-10T00:00:00.000Z/2017-07-10T01:00:00.000Z

This is exactly where QGIS TimeManager could come in: Using TimeManager for WMS-T layers. Interoperatbility for the win!